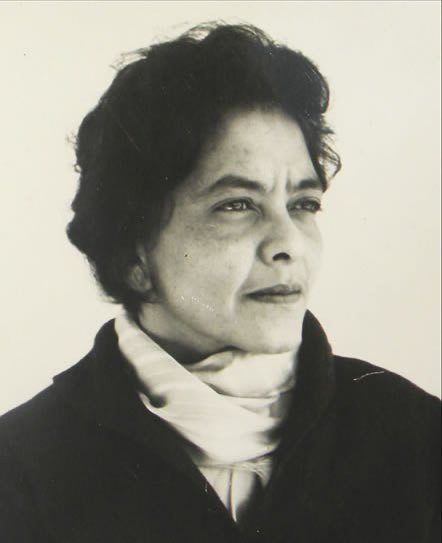

Enigmatic, reclusive in her twilight years, Zubeida Agha never ceased her lifelong engagement with her work, painting until the end. Her centennial year is a befitting time to remember her as one of the trailblazers of modernism in the subcontinent.

She had alreadymade an impressionin the years before Partition. A review of art in India and Pakistan by the art critic at The Statesman—at the time Charles Fabri, former curator of the Lahore Museum—described her as “that most remarkable artist of this sub-continent, Miss Zubeida Agha, a brilliant surrealist.”

Not everyonewelcomedthis defiance of convention though. Her works in the first exhibition of the Karachi Fine Arts Society in 1948 drew the ire of a critic who declared they would never have been included had he been the judge. At the time, N. Sen-Gupta wrote that such criticism assumed that “a painting, if it claims to portray something ‘real’, must represent the painter’s extreme effort to reproduce the visual form of that reality. Only those who fail lapse into abstraction.”

Looking at her early works of the 1940s and 50s, one can appreciate the surprise, even controversy, they generated. Only a supremely self-confident artist would have ventured so far from the prevalent sentimentalism of the Lahore School of Painting of the 1940s, which was closely aligned with the Bengal School. Some of Zubeida’s early works, like The Cotton Pickers, reveal the use of line and preference for pattern which was not unusual in that era. Her elder brother Agha Hamid, a bureaucrat and art critic, described The Cotton Pickers in his introduction to her solo exhibition in 1955:

The rigid intellectual discipline has resulted in a simplification of drawing and a rejection of unnecessary details. There is a deliberate but controlled attempt to simplify the structure of the painting and thus achieve a beautifully rhythmic quality.

This apt analysis holds good for almost all her lifetime’s work. Zubeida herself was averse to offering any explanation of her work.

Press article from The Statesman. “Art Development in India & Pakistan – Four Main Trends in Modern Painting”, 15 August 1949. Courtesy of Saira Ansari and Zubeida Agha archive.

N. Sen-Gupta, “First Exhibition of Art”. Pakistan: A Literary & Cultural Review. Autumn 1948, pp 79-80.

Agha Abdul Hamid, Introduction in catalogue for exhibition of paintings by Zubeida Agha, Karachi, 1955.

Females studying in art schools had not beenthe norm, but she was fortunate. Her family arranged for private art lessons, initially withB.C. Saryal, an eminent artist, and later, more importantly, with an Italian prisoner of war, Mario Perlingieri, a former student of Picasso introduced to her by her brother.

Her association with Perlingieri lasted only eight months, but left a deep impression. Under his exacting tutelage she learned to paint ideas, not pictures, tempered by her study of Greek philosophy, mysticism and Western classical music.As she put it, “The eye can grasp even the ungraspable, the invisible, if it is trained to see, and not just to look.”

Zubeida studied for a year at St. Martin’s School of Art in London before the artistic and intellectual milieu of Paris drew her to the École des Beaux-Arts where she flourished. She held solo exhibitionsin both Paris and London before returning to Karachi in 1953. Her homecoming signposted the next phase in her work and a fresh exploration of her palette, accompanied by references to motifs which emerged in her life in the burgeoning new metropolis of Karachi.

Zubeida moved to Rawalpindi in 1960 and soon after set up Pakistan’s first private art gallery which evolved into a pivotal space for artists from the two wings of the country—East and West Pakistan. Her keen discernment of fresh ideas made her a friend and promoter of young talent, bringing both modernists and young contemporaries together—Shakir Ali, Zahoor ulAkhlaq, Raheel Akbar Javed, Ali Imam,Zainul Abedin, and Mohammad Kibria.She had always recognised an exceptional vision when she encountered it—as a young girl, she had admired the work of the charismatic Amrita Sher-Gil, a close friend of her brother.

For sixteen years she worked tirelessly at the gallery until her move to Islamabad,by which time she was established as thedoyenne of the art world.

Over the following decades, Zubaida worked with great consistency and commitment in her studio. She kept a sharp eye on political, social, and cultural events around her, but nothing in her work overtly reflected the tumult in the country. Her paintings remained deliberately focused on the act of painting, her works deceptively simple but subtle inthe inventiveness of drawing in references from the outside world, every stroke laid out with clarity and careful spatial arrangements.

She had moved away from the often sombre earthy palette of her early practice and was now investigating a range of imagery. The process of developing the imagery, she said, was when “you get hold of an idea and you want to translate it in abstract form. That is how it starts. I used to take down notes and then think of forms and lines to express that in colour.”

Zubeida was particular about stretching her own canvases, meticulouslypreparing the surface with oil grounds and layeringpaints and pigments to achieve atranslucent glow. She never used varnish, ensuring the intensity of the colours which remain as true today as when she worked on them.The longevity of her paintings mattered to her.

Her passion for colour relationships led some of her contemporaries to label her a ‘colourist’. She herself rejected the epithet ‘woman painter’, confident that she had carved her own niche as ‘a painter’ and gender was irrelevant. She did concede, however, that a certain sensitive delicacy in colour might owe something to her gender. She added that political opportunism had been apparent in the work of her male colleagues, but that “women…are less willing to compromise.”

In defiance of age and frailty, her work grew ever brighter and more forceful as Zubeida continued to paint in seclusion in her Islamabad studio. She once described her paintings as “hiding a lot”, referring to the layer upon layer of paint painstakingly applied untilthe desired effect was achieved.And in much the same way, the nuances of Zubeida’s single-minded immersion in her work and her fiercely independent spirit engendered a mystique that endures to this day.

Note:

This article is based on an interview with Zubeida Agha by Salima Hashmi in Islamabad.